Going for a walk in a ZigZag gives visitors a chance to get lost and be surprised

When planning his new in situ work for EMMA, French art rebel Daniel Buren tried to stay away from the 100 meter window facade. Still, he kept coming back to it.

It almost seems like a blink of the eye from Daniel Buren to the museum visitor. If the visitor stands in the right spot and looks through a series of windows, they can see a glimpse of red and white stripes. And not just any stripes but ones that are precisely 8.7 cm wide, which have served as a repetitive element in the work of Buren for over 50 years.

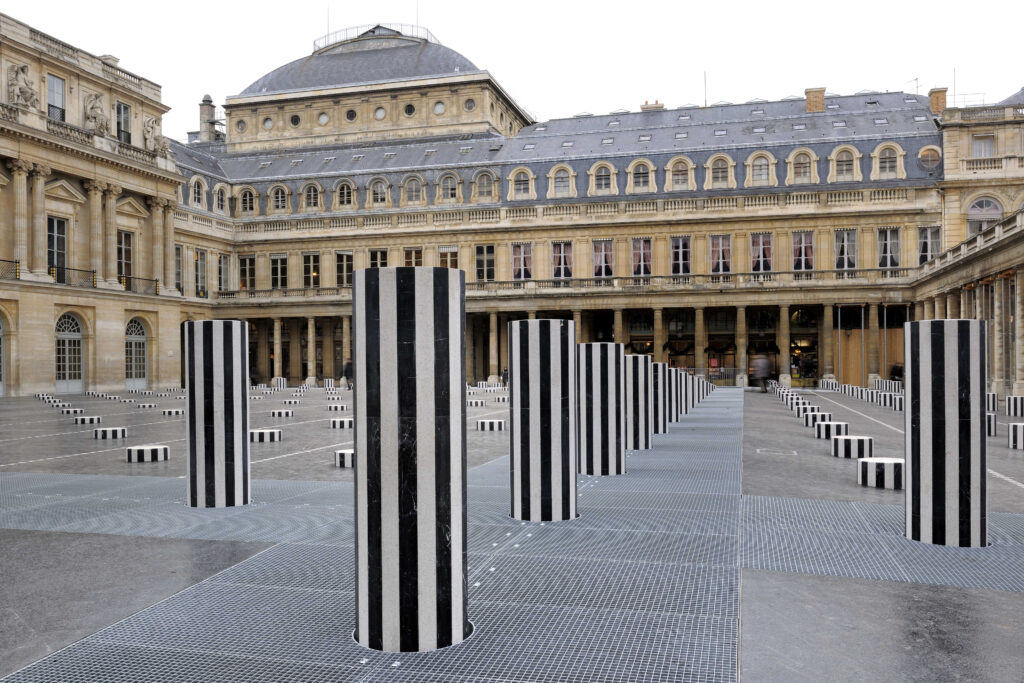

Buren, whose exhibition Going for a walk in a ZigZag at EMMA just opened, has taken his famous stripes to the streets, galleries, museums and back on the streets again – putting no more value on institutions than the everyday surroundings of people. Actually quite the opposite: especially during the early years of Buren’s career he was vocal about his critique towards the pretentiousness of art institutions of the time.

It was by accident that the stripes became a part of Buren’s toolkit. When visiting a market in Paris in 1965, a fabric covered with 8.7 cm vertical stripes caught Buren’s attention. Eventually, they became a visual tool used to transform spaces and places into in situ works. Buren has insisted and still does that stripes are meaningless, a priori, and only given meaning in context. Buren gives an example.

“Take a red light. If you see one in the middle of the forest, you might be surprised but will not stop walking. On the street, you would stop. By itself, the red light has no meaning,” Buren explains.

Now the stripes have been used in most of Buren’s over 3000 works, taking the such forms as fabric, furniture and posters, exhibited inside and outside of museum and gallery walls, constantly bending the boundaries of where art starts and where it stops.

“The time changed, I changed, everything changed. But this tool is still the same.”

The latin phrase in situ means working on site. This means that Buren’s work is not imposed on the space, nor does it work in dialogue with its surroundings. Rather the work stems from the place or is the transformed space.

However, even if in situ is most easily perceived through an architectural point of view, the practice should not be reduced only to that.

“As soon as the site is touched, so are the people working there, the people visiting, the history of the place and the politics of the time,” Buren explains.

In situ, on site, becomes in situation. The site, when understood from a very wide angle as Buren does, is the only reason and spark for Buren to start working. Therefore, even now as a celebrated artist, Buren doesn’t have a studio.

“What would I do with a studio? Sit there all day long with my blank paper? I arrive at a place, start to watch around and study the possibilities that open up.”

Daniel Buren

After having been invited to exhibit at EMMA and visiting the site for the first time 3.5 years ago, Buren was immediately drawn to the enormous windows facing north-west in the museum but felt like they were too obvious of an element to be used.

Still, Buren kept coming back to them.

“Now the windows are my point of reference to building everything else in the space,” Buren says.

The 100-meter long window has been covered with triangle-shaped translucent colourful sheets, which are reflected on the surfaces surrounding it. Buren has turned the exhibition space, known for its openness, into a large labyrinth where visitors can take different routes, get lost and be surprised. The work gets its name, Les Paravents (Folding screens), from the large folding screens dividing the space.

During the spring, the exhibition will spread outside the museum walls with a line-up of open-air events and interventions. In May a regatta will take place and an open-air piece of 105 striped flags will fill Espoo’s Tapionaukio square.

Buren’s stripes can also be spotted on the museum attendants’ vests. Printing them, a seemingly easy job, turned out to be more challenging than expected. To keep the orange 8.7 cm stripes intact, Buren had to work hard to find a material that would not shrink or stretch. The designer Sini Villi coordinated the production of the vests with the museum team.

“Buren is very precise about his tool,” confirms Arja Miller, the chief curator of EMMA and Buren’s exhibition.

When asked about what it was like working with Buren, Miller immediately mentions long conversations with Buren – not just about the work but also the state of the world. It makes sense as in situ covers the people working in the museum and the world surrounding it.

In a way, the exhibition started already a week before the official opening when over 300 JCDecaux billboards around Helsinki and Espoo were filled with stripes: five different colour combinations, without any reference to the artist or the exhibition.

In this way, Buren likes to play and challenge the idea of what we see as art. Does a striped canvas become art when taken to the museum context?

It makes the artist smile when thinking about the puzzled and surprised faces of people walking down the street and seeing the stripes.

“Even if I have been working for a long time, they won’t know the connection. It’s very close to my work in the streets of Paris already in the 1960s.”

Visit EMMA – Espoo Museum of Modern Art at Ahertajantie 5, 02100 Espoo. With its 5000 square metre exhibition space, it is the largest art museum in the whole of Finland. The exhibition is on until 17 July 2022.