In conversation with concrete roots—Aalto2 makes way for skateboarding

An interesting mash-up boasting street style and traditional design is currently on show at Aalto2, the unique meeting place for architecture, art and cultural heritage in Jyväskylä. The Pool – The Origin of Pool Skateboarding tells the story of the current top Olympic sport from an unexpected, and surprisingly Finnish, angle.

It all started with a kidney.

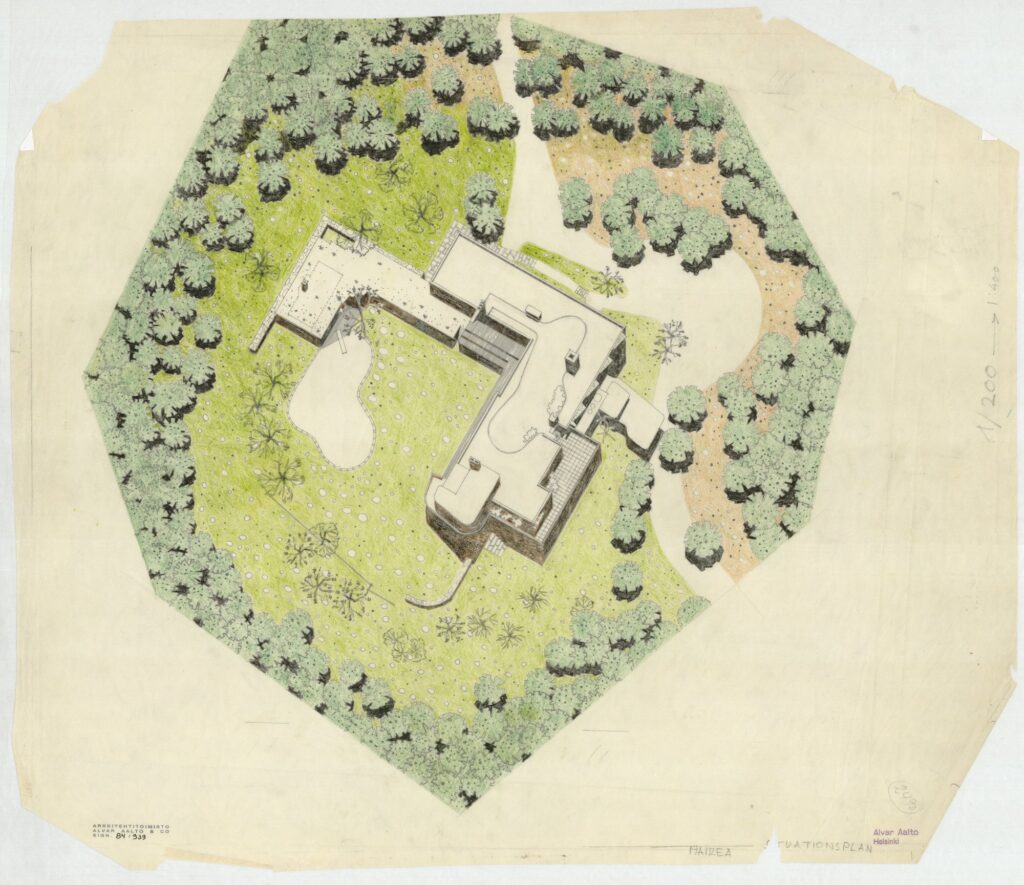

Not the organ per se, but its form, when Villa Mairea, the beautiful brainchild of Finnish architect Alvar Aalto was built. Featuring a kidney-shaped pool, believed to be the first of its kind, Villa Mairea became an architectural piece of wonder. Something which even California-based landscape architect Thomas Church came to admire. A wonderful occurrence, which through a set of random occurrences would later form the basis of modern skateboarding in North America. A slightly speculative narrative, but “the basis of the tale is highly factual,” claims Juho Haavisto, one of the curators behind the exhibition.

“While we have no concrete evidence, the Aalto influences in Church’s work are strong, and it would be nearly impossible to think that he would not have been familiar with Villa Mairea and the infamous pool form,” Haavisto clarifies.

The pool in Villa Mairea is considered to be a freeform pool, a pond style flowing in design with no particular shape, rounded edges and large curved areas.

A form which later featured in Church’s own work, particularly in Donnel Garden, a Modernist icon located in Sonoma, California. Completed in 1948, some ten years after the completion of Villa Mairea, the garden became famous for its unusual, abstract forms. According to the Cultural Landscape Foundation, frequently photographed, the garden came to stand for modern Californian living taking place indoors and outdoors, with fluid transitions between the two. Designed at a time in which California’s economy was booming and its population rapidly increasing, Donnel Garden became a symbol for the rise of the middle class.

Until a dry spell hit.

In 1975, the state of California experienced an unprecedented drought, to which locals responded diligently. Restaurants offered water only upon request, cars were left unwashed and people placed bricks in toilet water tanks in order to use less water. Under such conditions, all the pools, including the freeform ones, were left unfilled. A condition, once met by skateboarders, became creatively utilised. New tricks were invented in these brand new playgrounds, many which are still being done 50 years later.

All because of Alvar Aalto?

“Modern skateboarding has been influenced by two key factors. It all started with surfing, but another, lesser known influence was the freeform swimming pool designed by Aalto. As a result, the state of California, with its numerous swimming pools, became the Mecca of skateboarding. The Villa Mairea pool was built in 1938, and eight years later, the first kidney-shaped swimming pools were completed in California. When the sea wasn’t always wavy, surfers began searching for empty pools to skate in, as the curved edges of the pool resembled a wave,” explains photographer and skateboarder Arto Saari. “Empty pools which were prominent in times of drought.”

Saari’s photographs are featured in Concrete Currents – one of the exhibitions that builds onto the concept behind The Pool – The Origin of Pool Skateboarding.

“I presented the idea of an exhibition featuring skateboarding to the Aalto Foundation a few years ago,” recalls Jarkko Lehtopelto, curator behind Lizzie Armanto: Colors, which presents skateboarding culture through the eyes of the well-known Finnish-American professional skateboarder Lizzie Armanto. As its name suggests, Colors explores the diversity, inclusivity, and vibrancy of skateboarding. The perspectives include locations, tricks, boards, and communities.

“And Lizzie is a true Aalto fan!”

“In a way, there are three exhibitions in the overall exhibition concept: Arto’s photography exhibition, Lizzie’s collages featuring the life of a pro skateboarder, and then the historical section featured in From the Surf to the Sidewalk – When Skateboarding Culture and Architecture Meet,” explains Haavisto.

According to Lehtopelto, “When I presented the idea to the foundation, I never considered these perspectives. Instead, I thought the story behind the pool and its influence on the current Olympic sport was fascinating, and something which should be considered general knowledge, particularly in Finland. I also thought that a museum that represents architecture and design should showcase the creative reuse that occurs when a community begins to reinterpret spaces or objects in a new way, altering their intended purpose. That’s an interesting spin-off. Alvar Aalto is also very known for practical solutions—this exhibition, in a way, completely bypasses that.”

“I also thought that a museum that represents architecture and design should showcase the creative reuse that occurs when a community begins to reinterpret spaces or objects in a new way, altering their intended purpose. That’s an interesting spin-off. Alvar Aalto is also very known for practical solutions—this exhibition, in a way, completely bypasses that.“

“Meanwhile skateboarding is a sport that is starting to have some history. It plays a huge role among both young people and older generations. It is great to see the sport getting more widely accepted. Growing up, there were not many skateparks around, we were always outcasts. Just pushed to the sidelines,” says Saari. “But skateboarding is so much more than just a sport. It has always been, and will be, a subculture. More an art form than an athletic performance.”

Lehtopelto concurs, “One of the most interesting aspects of getting to know skateboarding better through the exhibition has been to see how skateboarders explore the urban environment. You can constantly view the city based on its usage. This way, skateboarding is continuously connected to the streets, architecture and culture.”

According to Arto Saari, former professional skateboarder, the sport is in fact a form of self-expression. Something which often involves a certain anarchistic spirit.

“It has nothing to do with results or accomplishment. Like if you think of it, what are you actually doing with your time, wasting it? Exactly that and this is the beauty of it.”

But seemingly easy, skateboarding requires presence, tolerance and concentration.

“You are constantly connecting with your surroundings, looking at each concrete surface. You look at every road, every nook and every pebble. Does that wood work to slide on? A skateboarder will look at the city like a giant fun park and that is where architecture steps in. It makes sense to bring it all together in an exhibition.”

“A skateboarder will look at the city like a giant fun park and that is where architecture steps in.“

From the museum perspective, there has for the past thirty years been a tendency to work with minorities and other groups that might remain invisible to the mainstream. It has, according to Ilja Koivisto, curator behind Concrete Currents, thus been natural to offer perspectives from groups such as skateboarders themselves.

“Research is conducted from a cultural anthropology perspective, but in collaboration with the people and the skateboarding communities. It is essential to work together with community members because you can’t fully explain the sport or its phenomena without insider knowledge.”

The overall setup is an interesting collection combining all three spaces of Aalto2 and the Museum of Central Finland.

Were there any complications joining these culturally prosperous parties with the rowdier, sometimes even rebellious skateboarders?

“There were absolutely no problems!” claims Koivisto laughing. “Although at the vernissage somebody might have done a trick on the statue by the museum café’s terrace.”

“Now that I think of it, the little fountain for the old stream running from Köyhälammi by the museum was empty most of the summer and during the exhibition opening. I wonder if anyone ended up skating it?”

The Pool – The Origin of Pool Skateboarding Exhibition at Aalto2 Museum in Jyväskylä is open until 15 September.