Designer Noora Yau sees change in the loopy rings of structural colour

Structural Colour Studio dives into the future of fashion and design through microscopic nanostructures.

From a young age, Noora Yau loved shiny things. To a child’s eye, everything from peacock feathers to seashells, butterfly wings and fish scales looked mesmerising. What puzzled young Yau was the fact that transferring such colours onto paper never worked. How come watercolours did not shimmer the way nature did?

“It has since then become clear to me that what we are dealing with is different mechanisms of colour formation,” Yau smiles.

The designer, who works with colour and material at the Structural Colour Studio, aims to explain the fairly challenging phenomenon calmly.

Structural colours refer to colours that are created through the interaction between microscopically small nanostructures and light. When light hits the material, it generates reflections that the eye perceives. For example, the nanostructures found on a butterfly’s wings produce vibrant hues and make the colours shimmer in sunlight.

Unlike traditional pigments, or absorption pigments, such as those found in store-bought watercolours, that create colour in a different way. These interact on the electron level so that when light hits the material, some of it is reflected and some is absorbed. The reflection occurs randomly in multiple directions, which makes the colours seem more matte and less shiny.

“What I have learned from colour theory is very much onnected to how the aforementioned absorption pigments work. The colours we are now studying, however, function in a completely different way,” Yau explains.

A simple example of rethinking colour theory could be that with absorption-based colours, we’ve learned that mixing blue and red creates purple. Structural colours do not work like that, and they cannot, for instance, be mixed in the same way.

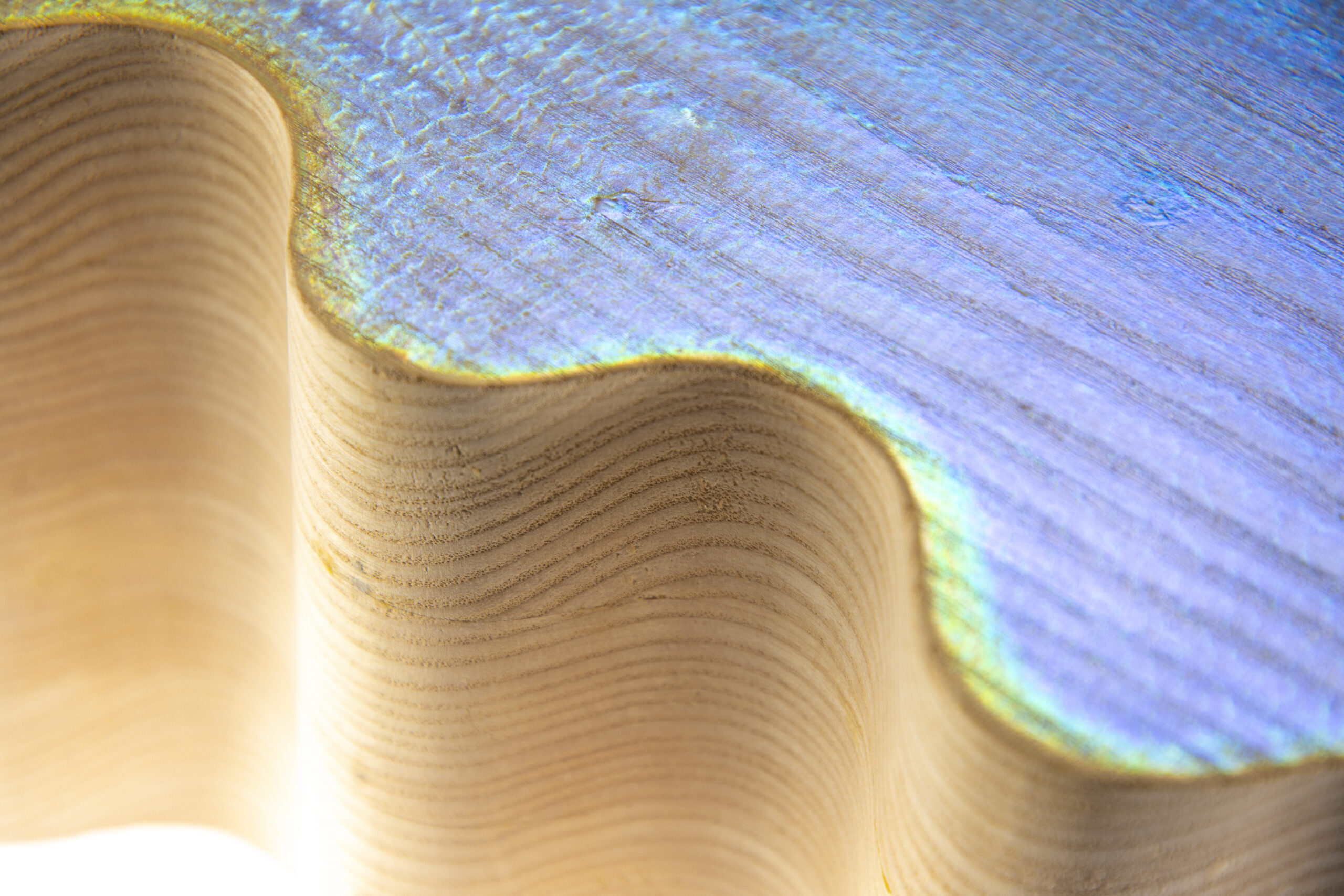

Having recently submitted her doctoral dissertation at Aalto University, Yau creates structural colour from nanocellulose together with materials researcher Konrad Klockars. Nanocellulose, derived from wood, is a non-toxic, renewable, and environmentally friendly material that is able to form the nanostructures necessary for structural colour. “If you know how to work it”, that is.

An exciting process that is all about learning new techniques, since creating shimmering or iridescent colour has proven to be an unpredictable task. “When we first began making colour, we were not able to produce any at all. What came of the first tries could best be described as transparent cellulose film. A dried glue kind of brittle, dry crust,” Yau laughs. A lot ended up in the trash.

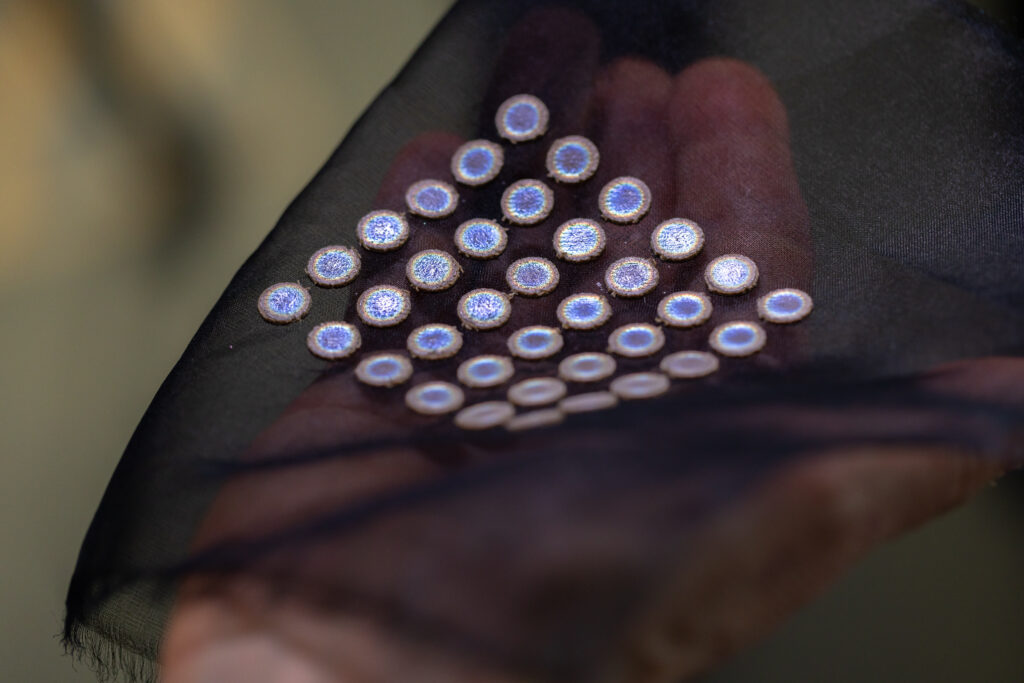

“When we finally managed to produce some kind of colour, I was thrilled. At the bottom of the three-centimetre Petri dish was the tiniest of rainbows.”

The collaboration between Klockars and Yau brings together science, art, and design in a completely new way. When creating colour, it is crucial that design is brought in from the very beginning of the development process, since even small changes in the colour recipe will have an effect on its nanostructure. And thus, consequently, the type of colour that ultimately becomes visible.

Including the presence of design and designers is important among other things because, according to Yau, materials scientists are not trained to perceive and consider the aspect of aesthetics in a similar way. They understand how colours work in a specific context, but often in a purely functional way. “In material engineering, colours might be developed for applications such as electronic sensors, where the nanostructure of colour reflects light as evenly as possible to ensure optimal technical performance.”

In such cases, the visual quality of the colour is irrelevant; the goal is to produce the most uniform surface possible. “There is a lot of research focused on achieving perfectly smooth surfaces.”

While that is important, it is equally essential to consider the inherent aesthetics of colour, Yau emphasises.

“For example, the colour that we have created forms these beautiful halo structures. Ring-like deposits that look something like coffee rings. Yet it is an effect that is despised in materials science to the point that efforts are made to eliminate it.”

In the hands of Yau, the unwanted ring becomes a discovery: a naturally forming highlight effect. Something that could be used, for instance, to accentuate the shape of dyed surfaces.

While from the perspective of traditional design, it could be hard to understand what could be done with such tiny rainbow samples. The collaboration between the designer and the materials researcher thus, creates ample opportunities to explore things that might easily go unnoticed.

The collaboration between the designer and the materials researcher thus, creates ample opportunities to explore things that might easily go unnoticed.

“Through collaboration, we aim to make the material development process as holistic and comprehensive as possible,” Yau says.

Since fashion designer Anna Semi joined the Structural Colour Studio, the operation continues to expand further. “We are now fine-tuning the material. The goal is to bring it into commercial applications.”

The trio is focusing on the fashion and design markets in particular, as those have the ability to highlight and bring things into public conversation.

“Ultimately, we want to create these colours because the current ones are made from plastic, metal, and other toxic substances. They are very harmful to both people and the environment.”

A tangible and understandable goal to say the least.