Design can create happiness for future funerals

Service designer Marja Kuronen studied death and future scenarios for funeral services and noticed that our tradition is at a turning point. Instead of standing stiff by the grave, many of us would like to gather and recall happy moments or even arrange a party to pay tribute to the deceased.

Service designer Marja Kuronen studied death and future scenarios for funeral services and noticed that our tradition is at a turning point. Instead of standing stiff by the grave, many of us would like to gather and recall happy moments or even arrange a party to pay tribute to the deceased.

During the last couple of years service designer Marja Kuronen, specialized in wellbeing and joie de vivre, has been studying death. Or more specifically: she has studied the future scenarios of burial services based on design thinking and development by future awareness.

In practice, this means surveying the operational models, values and current conditions of the funeral field as well as the wishes and needs of the customers, i.e. family members and organizers. Kuronen found her topic accidentally as she was looking for material for the blog of her mother who has been working in terminal care. The topic runs in the family, so to speak.

“I’ve always been interested in designing around loss, I mean, how people deal with loss and how our values and lifestyles relate to it. As I was looking for topics for my mother’s blog, I realized that during my service design career, I’ve never heard of service-designing matters related to funeral arrangements or the death of a family member,” Kuronen explains.

She also notes that service design is easily understood only as a way to improve business. However, design thinking can be used to impact society and social issues at large. At best when addressing burial design.

“Death is addressed in pop culture and art, but when a family member dies, people are faced with matters they don’t really understand. This is because death has been swept aside from our lives to hospitals and morgues. This may sound macabre, but I wish death and burials could gain more ground in people’s daily lives,” Kuronen says.

Death and happiness

Before Kuronen gave a lecture at the Arctic Design Week the presenter of the event Päivi Tahkokallio, a design professional from Rovaniemi asked: “Death brings up controversial feelings. But can happiness be associated with death? What does it mean in the context of burial services, and how can it be achieved for the deceased?”

This is a complex question for Kuronen, too. She mentions having thought about a service to design one’s own funeral in advance online. She thinks the knowledge of being able to adjust one’s funeral to one’s own liking can create a feeling of happiness before death.

“The Finnish union of undertakers does actually have a form to fill in to plan one’s funeral. But according to my view, it’s more like a shopping cart which family members can use to make an order later. Updated to modern times, the service could consist of a digital platform on which to select your favourite music or an urn made by a local artisan and place an order for the moment when your family members enter the service,” Kuronen suggests.

“Many people organizing funerals are under a lot of stress about making the event the way the deceased would have wanted. This easily creates disputes among relatives. Having everything decided in advance could make things easier for the family,” Kuronen says.

For the family, happiness can be created by the funeral service provider, too, by providing genuine understanding of their situation and giving them a voice and a vision.

“The grieving relative must be offered relief, and the services must be designed according to their values. Experiencing loss does not rule out feeling relieved or happy, too, which can be promoted by design thinking and future-aware development,” Kuronen assures.

Dying a little

Kuronen knows that people’s behaviour and wishes in terms of funeral services are at a turning point. The causes are many and relate to global megatrends, such as digital lifestyles and urbanization, the new ways of consumption, the depletion of natural resources, the ethical and ecological demands, as well as the growing multiculturalism. However, the change has not been embraced in Finland yet.

“Where digitalization, AI and smart materials are becoming a standard in many other fields, they are not present in the Finnish funeral business yet. There have been major changes in other countries, however. For example, there is a service in California that lets mourners drive through to the coffin like in a fast food restaurant. I don’t know if this would fit the Finnish culture, though,” Kuronen says.

Therefore the question is: does the funeral field need to keep up with the times and trends? Not necessarily, if we believe the latest results of the Finnish undertakers union’s survey. The results indicate that customers, i.e. family members, are happy with the services throughout the country.

“My own study conveyed the same results to begin with. Based on the responses, everything is fine, particularly regarding the undertakers, and there is very little need for development. However, people were not as happy about hospital and church services,” Kuronen notes.

These results were just an interim report. Like dying a little before getting to the heart of the matter.

A great party by the grave

When Kuronen made her survey more specific, the results flipped. She targeted the generation that will be using burial services in the future, i.e. 30-to-40-year-olds, and the results indicated a need for a change.

“My interest piqued dramatically when I noticed how poorly burial-related services meet the needs of this age group. As stated above, these people will be organizing more and more funerals in the future,” Kuronen adds.

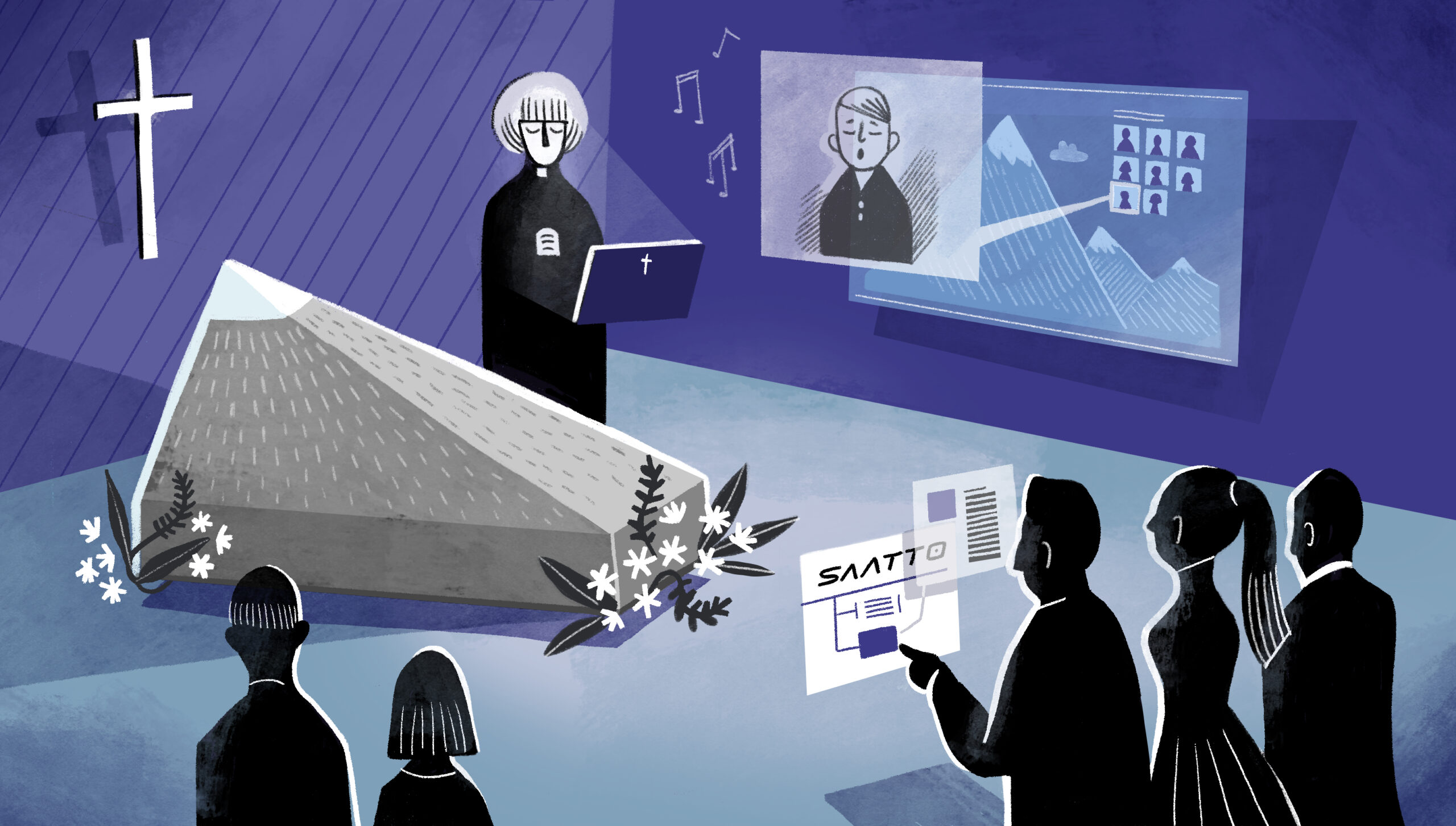

According to Kuronen, this is the age group that wants to make orders and plan events online, participate in a funeral remotely from another country, for example, and implement more individual solutions with the arrangements. The survey also found that this age group is rather estranged from the church but feels strongly about nature. Then again, they gravitate heavily towards the community when dealing with grief.

“People have a strong need to decide about their own funerals. Many wish there was some kind of a digital platform by which to make personal choices, for example regarding social media profile management after death,” Kuronen says.

Many of the respondents said they want to break the current formula that feels old-fashioned: standing stiff by the grave, grieving silently for the person who has passed. The current formalistic ceremony represents a culture that is far from the target group’s values and lifestyles. Many felt this is not an appropriate way to pay tribute to the deceased.

“People now wish they could gather and recall the happy moments spent with the deceased when he or she was still alive. I also found that people want their own funeral to be a great party. Unfortunately, as far as I know, no Finnish undertaker offers this kind of service,” Kuronen says.

The new forms of death

Although funeral traditions as well as attitudes towards death are very much related to culture, they have indeed changed over time. Kuronen points out that funerals used to be a community event in Finland, too. Now the number of attendants is declining and priests end up uttering in memoriam alone.

So, what is the real problem here? And what kind of solutions can design professionals provide?

“Through in-depth interviews during my study, I understood that we need new kind of rituals to handle loss. Our current systems are outdated and do not serve their purpose in a digitalized, widely reformatted environment,” Kuronen explains.

After analyzing future scenarios for the funeral business, Kuronen notes that there are many different directions to take. Together with burial service providers, service design professionals can influence the way funerals – and death itself – will appear in the future.

For example, perhaps florists could organize wreath and memorial workshops for the mourners? Could the relatives living abroad participate the funeral remotely through a digital platform or channel? How could our longing for nature and sense of community be met in future funeral ceremonies? What about global megatrends, such as our objectives for ecology and sustainability?

“Various concepts and services related to burials have already landed in Finland. Composting the dead body is already possible in some parts of the world, and in Japan, some function like wedding planners to organize funerals. In some places, artificial intelligence has been harnessed to gather memories and relieve the different phases of mourning,” Kuronen lists.

She notes that although the traditions of different cultures do hold up, the consequences of globalization are becoming increasingly visible: the trends, values and attitudes intertwine and impact the needs and wishes of people as mortals. Kuronen believes that the many new ways in which technology can help deal with loss will gain popularity.

“We have to understand the needs of the future and customers on a deep level. This applies to any field. We need to think how relevant the services and products are to customers and users while also considering how to support ethics and ecology,” Kuronen concludes.

She lectured on the subject in March at Arctic Design Week in Rovaniemi. This year’s theme was design for happiness. Kuronen ended her presentation in a brilliant note that crystallizes the core message of the 7-day festival targeted at business and design professionals and design students:

“The future is easy to predict if you are one making it.”