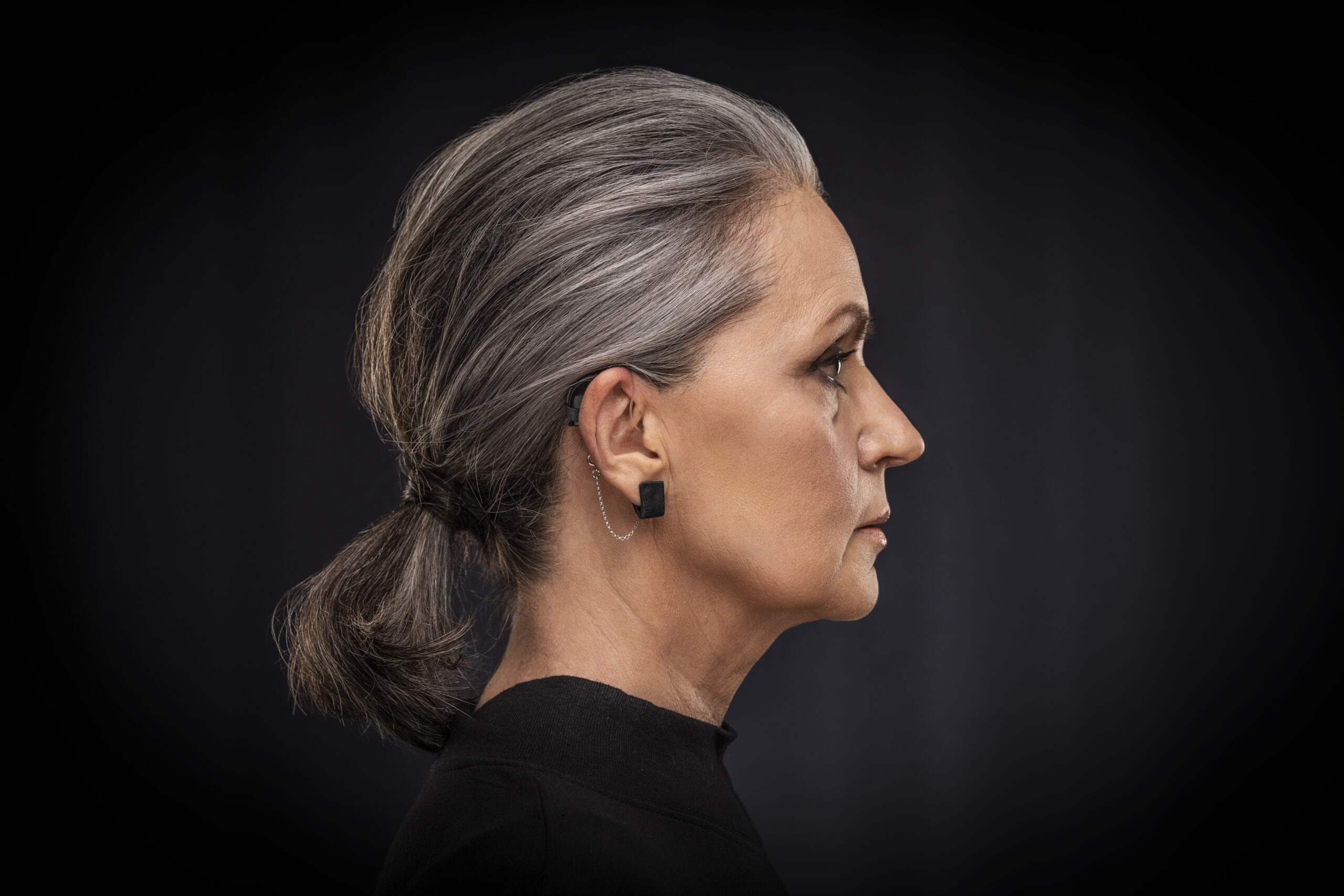

Designer Jenni Ahtiainen on allowing technical aid users to look like their personal selves

AIDesign by Jenni Ahtiainen focuses on making technical aids personal. She believes that an instrument such as a hearing aid can be both necessary and beautiful, just like the person carrying it.

AIDesign by designer Jenni Ahtiainen focuses on making technical aids personal. The idea is that an instrument such as a hearing aid can be both necessary and beautiful, just like the person carrying it.

“This is the most important task I have ever taken on,” confirms Jenni Ahtiainen. She sounds confident.

Two years ago the designer founded Deafmetal, a jewelry collection for hearing aid users – and a lot has happened since. Ahtiainen first burst into international recognition through her fashion brand gTIE. She spent years designing accessories for world class celebrities.

Life, however, had other plans as the designer’s hearing suddenly declined rapidly in 2018. Everyday communication became harder by the day, and Ahtiainen’s life was thrown into a new direction. Little did she know, this personal adversity would be the start of something very good.

Freedom of choice

At first, the hearing aids felt foreign. In fact, the whole diagnosis had been a shock. Ahtiainen’s hearing had weakened so much that she now needed hearing aids in both ears. Trying on her first pair of hearing aids in August 2018, the designer decided to make them look more personalised, more like herself. Quite naturally she went to work and began designing accessories out of black leather. When the first pair was ready, she posted a photo on social media.

“I just wanted to tell the world that ‘Yeah, I have got hearing aids but that’s OK. I made them look like jewelry,’” Ahtiainen says. She had no idea how positive the response would be.

Jenni Ahtiainen’s social media photo spread like wildfire! To date, over 220,000 people have seen the image.

Ahtiainen says, “That is when I realized that hearing aid users are often left with a certain amount of aid guilt as they do not get to choose what the apparatus itself looks like. Much unlike when choosing glasses, for example. We are left at the mercy of the device.”

Large hearing aid producers are already using a lot of resources on aesthetics and design, but completely lack the ability to personalize the products.

“The most important innovation of Deafmetal is not the jewelry itself but the functional part, which enables the attachment of the piece onto the hearing device,” the designer reinforces. “I am not out to reinvent the wheel but to give users a chance to truly make these devices their own.”

Designer hats for blood glucose meters

The designer first began her work on hearing devices but quickly expanded into cochlear implants. For these small electronic appliances that electrically stimulate the nerve for hearing, Ahtiainen designed convex casings.

Furthermore, she expanded this idea into the Sugarhatty product series aimed at diabetics. The idea grew from a fortunate encounter with a client who wished to cover a sensor attached to the skin for a party.

The delicate nature of the device set the framework. Ahtiainen needed to make something that was light enough for the coin-sized mechanism to stay on the skin – and allow for the digital reading of blood sugar values.

At first, Sugarhatty looked very much like its creator, a bit rough. Soon enough, however, the designer started stepping out of her comfort zone.

“My assistant was a bit surprised when I started pulling out all these pink and golden fabrics,” Ahtiainen laughs. “But all my designs are born through customer interaction. When someone dares to wish, I create.”

No need to cover up aids

Deafmetal has gained a lot of interest in the media and has won several prizes both in Finland and abroad. More important than fame, according to Ahtiainen, has been the feedback from customers. “I had a client who had for years been growing their hair in order to hide the hearing aid. Now they instead decided to shave it all off so the world could see. That feels incredible.”

According to Susanne Jacobson, PhD in Industrial and Strategic Design, who wrote her dissertation on the personalization of aids, an aid will always express, mould and build the user’s identity. Some also feel that using one will label them in social situations. Jacobson states that design has a crucial role in cultivating how aid users see themselves and how they relate to society.

Ahtiainen is also very familiar with the everyday lives of aid users. “The fact that someone has a hearing aid will affect the discussion or even determine whether one will be had in the first place. One client told me the jewelry I created has a fun way of drawing attention away from the aid itself.”

Design becomes more human

In January 2020 Ahtiainen took a step in a new direction by registering AIDesign, a company solely focused on personalizing aids.

The designer plans on expanding into the international market and onto new devices. She tells about the process of designing gloves for those suffering from rheumatism and joint problems, while sleep apnea patients could soon be getting personalized breathing masks.

In addition, Ahtiainen has been building the Instagram-based Deafmetal Community group. The group began showing unique images of art and beauty in order to make hearing aid users more visible – and thus, more socially accepted. “We are basically reinforcing the fact that seeing someone with a hearing aid is comparable to seeing someone with spectacles,” Ahtiainen says.

In the world of fashion, aids are still non-existent. Walkers, rollators and hearing aids are not frequently encountered on the pages of glossy magazines. Ahtiainen believes that the reason lies in the glorification of the concept of perfection, something which the fashion industry is largely built around. When a perfect life or body is portrayed, the image of a person becomes very narrow. An attitude change is still possible, Ahtiainen believes. There has already been improvement in the field.

“If we get enough actors in the field with new, more anarchistic views on the business and the way we portray the human body with all its faults and imperfections, then design will eventually become more human.”

This article has been produced in collaboration with the design journalism course of Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences’ degree programme in journalism in spring 2020. Like all content in Helsinki Design Weekly, the partner articles have been written to primarily serve our readers.

Featured image: Tapio Aulu