I think of 3D design, or at least how I approach it, as similar to photography, says Maisa Immonen

One of a new generation of young designers exploring design through augmented and virtual reality, Weekly Studio catches up with Maisa Immonen about 3D design, creating Instagram filters, and why she still likes working with ‘old-fashioned’ tools like paint.

Crystal Bennes: Could you start off by speaking a little bit about your background and how you got interested in designing for virtual environments?

Maisa Immonen: I started out studying graphic design at Aalto in 2016, but shortly thereafter I realised that graphic design isn’t really the field for me. There was a 3D course, or a course in 3D software, being offered at the school and I just became very interested in the 3D world. It seemed like a good space for me to explore. Eventually I moved from graphic design to 3D design and started a programme in XR design at Metropolia University of Applied Sciences looking at things like augmented reality and AR and VR.

CB: I’m curious as to whether you’re studying things like theory and philosophy or ethics as part of the XR design course?

MI: Not really. And, anyway, I’m a very bad student [laughs]. I suppose I mean that I’ve been focusing mainly on my freelance work and concentrating less on my studies. I haven’t been studying so much at the moment because I’m trying to find my own career path, navigating between graphic design and XR design at Metropolia. I’m not sure that I’ve found the right balance yet.

CB: Do the two different design fields you work in—3D and graphic design—do you feel that they have interesting things to say to each other, or do they feed into each other in meaningful ways?

MI: Graphic design is so much more about advertising and branding, and it’s very customer-focused. Whereas XR and 3D-design are usually more prevalent in the gaming industry and in the start-up world, so the cultures feel quite different. It may be that they have more in common than I think, but graphic design has not felt like the right place for me. The advertising world doesn’t hold a lot of appeal if I’m honest.

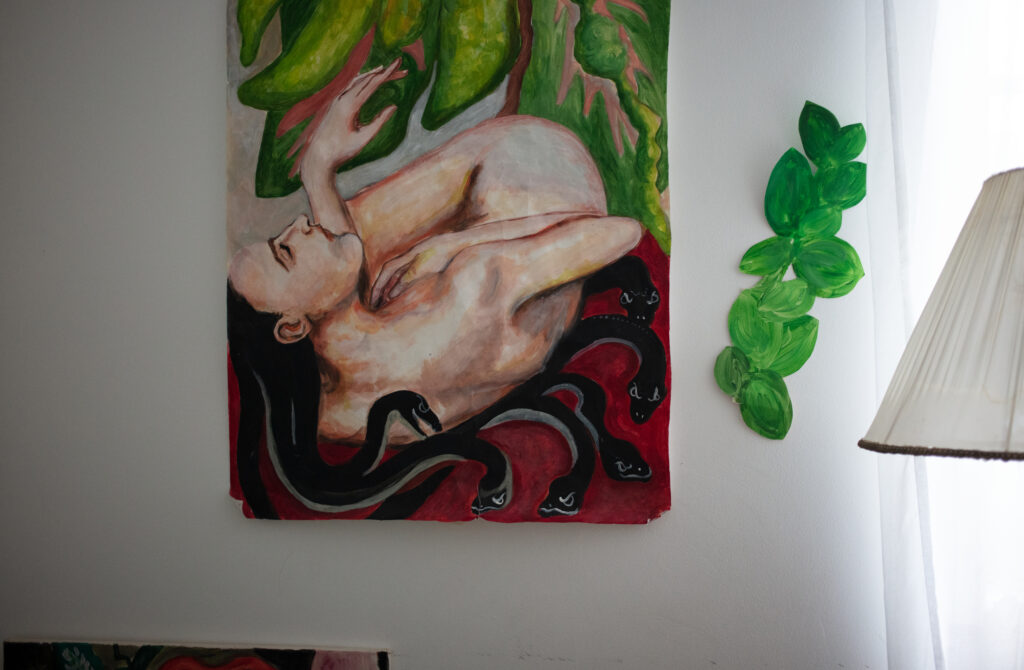

CB: What about fine art and design instead? I know you’re also very interested in things like painting.

MI: Yes, I’m very interested in fine art. I think that 3D design has more in common with fine art than with graphic design. I love to paint and draw and make rugs, but generally I find it much easier to sell 3D work than to sell paintings.

CB: The 3D world is something that seems very cutting-edge and brand new, but, for example, many designers work with 3D modelling as part of their design process, so it’s quite established technology in the design world.

MI: Yes, that’s definitely true. From my point of view, I think of 3D design, or at least how I approach it, as something similar to photography. It’s as if I’m a photographer and the 3D characters are like the models. I suppose the aspect that seems new is the widespread appearance of 3D technology in things like Instagram filters. Because Instagram has made filter programmes so wildly popular, I think designers have become more attracted to making them.

CB: It’s interesting that many of your digital characters look a bit like you. Has that been a conscious decision on your part?

MI: You’re not the first person to notice that, but I don’t think it was a conscious design to make characters that look like me. It might be that I make designs about my feelings, or that I use the characters to express different feelings that I’m experiencing, feelings like shame and strangeness; a way to express or work through some insecurities. It’s funny, though, because it’s so natural to me to create and design these characters, but it’s much more difficult to discuss or analyse them and their meanings.

CB: You mention these themes of shame and strangeness. Could you say a bit more about that?

MI: I’m originally from Seinäjoki, a small town that’s also a very religious place. I think part of my interest in shame and strangeness comes from this feeling, partly that stems from my childhood, of being afraid to be an outsider, being afraid to be seen as somehow different. Again, it’s very difficult for me to put some of these things into words, and that’s what I try to put into my designs, but I think it’s a very powerful fear in life. Equally, when I started to become more aware of this shame and its power, I was also able to redirect that power to transform it into something like a weapon. It’s really a very important theme in my work.

CB: Although it might be easy to describe your aesthetic as futuristic or sci-fi, plants and animals are visual elements that reappear again and again and I wonder why that is. Would you say that you’re very inspired by nature?

MI: That’s an interesting question. I’m not sure I’d really noticed the presence of natural themes in my work before. For me, nature is very symbolic in terms of growth and the circularity of life. Even though I work in a ‘high tech’ medium, I have always gravitated towards leaves and plants rather than a more tech aesthetic. I like green and I like growing power. I’ve always loved animals. But I equally like things that maybe other people would find a little bit alienating, for example images that combine human and animal. You know, like centaurs. I’m also a Sagittarius, so I tend to gravitate toward images of centaurs. I suppose I prefer fairy-tale vibes at heart.

CB: Do you create stories around your characters or are they more about visual experimentation?

MI: For me, it’s much more about playing with visual ideas than with telling or creating stories. Often the design work starts from a colour or texture, or even maybe a posture, that has inspired me and then goes from there.

CB: I can’t help but admire your beautiful cat! What’s their name?

MI: Kasper. I’ve had him for a year and he’s wonderful.

CB: In terms of some recent projects, I wanted to ask you about the work you did making filters for participants of the 2020 Untitled Festival. How did that come about?

MI: I know Roope Mokka, who organised the festival, and he invited me to make filters for them.

CB: And was there a specific brief, or was it quite open?

MI: It was actually remarkably open, although there was a direction because the festival was based around a futures theme, around how humans will live in the future. I started to think about what zoom meetings might be like in the future—because the festival was held entirely on zoom—and then I designed five or six different filters that participants could use on zoom to transform their appearance.

CB: I wonder if you’re thinking about things like gender, race and dis/abilities when you design filters for things like festival participants, or are you basing your designs mostly on yourself as a model?

MI: To be honest, I’m not really thinking about gender or anything else when I make filters. Maybe I should be thinking about it more. I suppose the thing I most think about is the extent to which filters almost automatically make skin tones lighter, so I have to think about that. Instagram filters originally came from beauty filters that do things like give people bigger lips or eyes and smoother, often lighter, skin. A lot of these filters are based in very conventional ideas of beauty and my interest has always been in subverting these traditional ideas of beauty to make effects that transform faces into something more playful and a little bit weird.

CB: You’re still in the relatively early stages of your career, but do you feel like you’re beginning to figure out how to balance commercial and creative or personal work?

MI: Yes, I think it’s working quite well right now, but I think it would be nice to get to a stage where I can be as experimental as I want, even in commercial work, with clients approaching me directly. At the moment, I’m part of a creative studio, but I think I’d like to continue to find my own way forward in the future.

CB: And what kinds of clients or projects would you like to be working on?

MI: I would like to make more face filters, but outside of Instagram. I’ve been learning some interesting techniques recently about how to track 3D objects to the face without using the filter technology from Instagram or Facebook and I think it would be nice to break away from those platforms as they’re so dystopian and monopolistic. I would also love to work on music videos or music campaigns. I’d really like to work on music projects.

CB: I know that you’re involved in something called the Post Human Dance Collective, which sounds fascinating. Have you been developing that still during Covid times?

MI: Yes, so it’s a collective with multi-disciplinary artist, Erika Rustamova, and musician Ossi Kolehmainen. We had the first event in 2019 at Kaiku, a nightclub in Helsinki, and the idea behind the collective is to experiment with post-human dance to think about and discover new ideas for what a club could be in the future. We’re interested in all elements of clubbing from the visuals to the music to the experience in spaces. But then Corona came and the clubs closed down, so we decided to try something completely different with a custom-built online virtual reality space. I created five different rooms, different worlds really, and then guests could come to the spaces with avatars that they could make themselves. For example, I created this centaur avatar. We had a lineup of different DJs playing and we streamed the event at Twitch. We’ve done this three times now and it’s been great.

CB: How does it compare from purely experiential point of view with being in an actual nightclub?

MI: I think one of the things we all really liked about the online space was that each guest could chose an avatar to come dressed up or as someone completely different to themselves. When we go back to hosting our nights at Kaiku, we’re thinking of ways that we can encourage something similar through costumes or dressing up.

CB: Just out of curiosity, are there other AR artists whose work really inspires you?

MI: I’m inspired by a lot of very different people, not only 3D creators, but also fine artists and musicians. But in the 3D world, I’m very inspired by Ines Alpha. She makes very beautiful and unique filters for Instagram and she’s someone I find very inspirational.

CB: Is Helsinki a good place to be based as a 3D designer?

MI: For now, Helsinki is quite a good place to be based in, but 3D design is really not a very well established field in Finland. In graphic design and advertising, it’s not extensively used. Who knows. Maybe in the future, it will be more sought after here.

I’m really interested in working abroad at some point. There are some very good places to be based as a 3D artist, but it’s not time for me to leave just yet.