Joints could be design history’s missing elements, says Anniina Koivu

Weekly’s Crystal Bennes met design writer, curator, consultant and teacher Anniina Koivu, co-curator of U-Joints. U-Joints is a research project and exhibition series on the topic of connections in design and architecture. We found out to what to expect in the next chapter: U-Joints: Knots&Knits. It’s one of the main exhibitions in Fiskars Village Art & Design Biennale (22 May–4 September 2022). What are the social and cultural histories and politics of the joints in question?

Weekly: Where did this interest in joints come from? And why both a book and an exhibition programme?

Anniina Koivu: Andrea Caputo and I have been good friends for a long time; he’s an architect and I come from design. In January 2018, we were having coffee after the new year and thinking about whether we should do something for the upcoming Salone (ed. note: del Mobile in Milan, Italy). The specific idea to look at joints arrived largely because it was something that had natural crossover for both architecture and design.

Having very little time until April, we decided to do something small for Milan. We contacted twenty designers, hoping that maybe half of them would show interest. But all twenty said yes, so we started building the exhibition from there. At that point, we found a larger exhibition space and so it grew into a large, eclectic introductory exhibition of more than 800 objects. These ranged from designer projects to custom-made joint models, but included joints from industrial producers as well. The show was hailed as an “unadulterated curatorial delight”, a “great show” and “ultra-nerdy”. “Every designer and design student should bring their sketch book and get down to basics,” wrote one critic. The positive response took us a bit by surprise, so much so that we felt we should turn it into a proper research project.

This is also when the book got started. Now four years later that it’s completed, the book is an encyclopaedic volume of 940 pages filled with essays, interviews, anecdotes, illustrations and photographic essays alongside a large taxonomy of joints. It’s organised in chapters where each chapter looks at a specific type of joint whether that’s basic fasteners, mechanical joints wood connections, knots and knits, adhesives or welded joints.

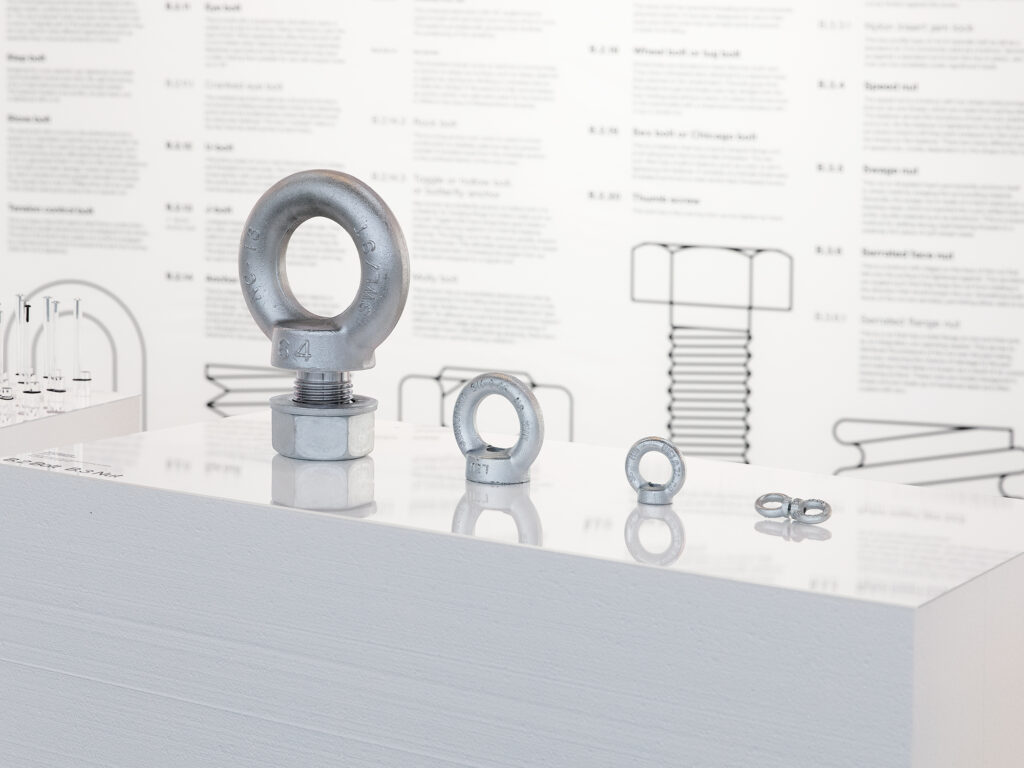

Because of this structure, it felt logical to conceive of the chapters and the exhibitions as complementary. Hence, we did the fasteners exhibition at ECAL in Lausanne Switzerland—about screws, nails, rivets, bolts and nuts and their applications. It’s always a combination of the joints and some application. There are furniture pieces and products, but also curiosities from various fields including architecture, aviation and medicine. At ECAL, for example, we exhibited a piece of an airplane which was riveted together. There was also a large wallpaper displaying hundreds of joints organised in a large taxonomy. This taxonomy, now including about 1,300 examples, has become an important part of the publication.

After the first chapter of basic fasteners, we made an exhibition at the Gewerbemuseum in Winterthur on the world of glues, sealants and welded and fused joints.

We still have a few chapters remaining, but we thought it would be nice to dedicate the Fiskars show to knits and knots. We also had a chapter on wooden joints available, but wood is something that is omni-present in the Nordics and so we thought it would be more interesting to bring the unexpected.

When you were discussing in early 2018 together, did you have a list of subjects of possible interest? Or was it always joints?

It was always about joints. The first examples that we had in mind were mechanical joints—clamps, springs, nails and rivets, scaffolding systems. But then, when we realised that we should also look into glues and other bonds, a whole different world opened up. So it evolved from one thing to another.

Anniina Koivu

How do you and Andrea work together? Do you do everything together or do you divide depending on your different strengths?

We couldn’t do all of this with just the two of us. It’s a very collaborative project.The research and the book were compiled by a large team of more than 120 authors, photographers and illustrators, scholars, designers and architects, artists, writers, dreamers and makers.

It’s a bit difficult to say with certainty as I haven’t seen either the book or the exhibitions, but the project feels very materially centered. Are you also looking at things like the social and cultural histories and politics of the joints in question. Knits, for example, typically have gendered connotations and associations.

The book would have only grown to half its volume had there not been the conviction that there is so much more to say about a joint than simply how it functions. In addition to defining types of joints, we looked at their histories, their human dynamics, their cultural origins and their impact on society. The book is full of interviews and essays, but also anecdotes. The anecdotes are where we reveal the stories behind an object or a joint that someone might not know.

As these are mainly text and image based, not all of them are easy to transmit into an exhibition. Early on, we decided that the exhibitions will always be object-led, almost like appendices to what we have in the book.

For the Fiskars Village Biennale, we plan to have a large taxonomy wall—a collage of images, videos, texts, as well as many material samples. The taxonomy is organised into sub-categories depending on which kind of joint we are talking about. So, weaving, knotting, knitting, twisting, braiding, etc. And then, we tell little stories attached to each of those, alongside various applications whether from design or from crafts or art.

If you’re interested in the cultural and social backgrounds, of course there are many. We can’t tell all of the stories that are in the book, but for example, we have stories like that of Philippe Petit, the man who walked on a tightrope between the World Trade Towers in 1974. We did an interview with him about knots that save lives, in places like the circus where acrobats are extremely dependant on knots. We’re going to show the five knots, of the 300 or so that Petit knows, which are the most important for tricky life situations.

There’s also the tragic story, which I find very beautiful, of Queen Mary of Scotland. Like all women of her time, whether royal or poor, she did a lot of embroidery. She often embroidered secret, sometimes political, messages in her embroidery, some of which were addressed to Elizabeth I, her cousin. It’s fascinating that something which we think of as so decorative can become propaganda, or a container of hidden messages that influences politics. I hope these stories will come through in the exhibition, too.

Half-way through this project it occurred to me that joints could be design history’s missing elements. Aren’t joints the microhistory in design history? Microhistory focuses on ordinary people and the peculiar moments in their everyday lives. In this sense, microhistorians view people not as a group, but rather as individuals who must not be lost within the historical processes or in anonymous crowds. But paying attention to the minor individual stories helps to draw connections to history’s general storyline and fill in some gaps. “Micro” shouldn’t only be taken as denoting the real or symbolic scale of the object, “micro” in “microhistory” should be understood as in “microscope”, an intensive approach to any topic.

Anniina Koivu

With respect to the book, which is frankly enormous, you speak of it as encyclopaedic, which can be a bit of a loaded word. I wonder about the geographic spread and how you chose the joints you’ve included.

The book includes examples from all around the world whether woodworking in Japan, welding in New York City or basketry in Borneo. Because we are concentrating on joints used in the making of design and architecture, we focus mainly on contemporary joints. There are some historical stories too, but it wasn’t our aim to conduct a comprehensive anthropological or geographic study.

Because we worked with experts from all around the world, many projects were proposed by our external authors. It has been quite organic how things came together, so I think that, although you try to be comprehensive to a certain extent, you also recognise that such a thing is impossible. True, the word “encyclopaedic” is sometimes misleading. The research and publication are encyclopaedic in their breadth and detail, but the book is not an encyclopaedia. Also we took the liberty to include rare curiosities, even one-off joints. That is the beauty of curatorial freedom.

Could you talk about the role of the external authors? Why was it important to bring in external authors?

We never had the intention to be the sole authors of such a large book. How could we. In Italian there is this term of the “tuttologo”, a know-it-all, which we are not. It is important to hear other people’s viewpoints, so we made sure to seek out the experts in their field. For some of the more anecdotal contributions, journalists have been perfect, but when we’re looking at technical details about how something functions, the historical origins of a joint, then we really needed to have a researcher or a scientist to transmit the correct information.

Can you give an example of the latter?

We have an interview with Mariana Popescu, who recently finished her PhD at ETH Zurich where she was researching 3D knitting and architecture. She developed a lovely project a few years ago, a pavilion for a biennale in Mexico. It was machine-knitted in Zurich and she was able to put the entire pavilion structure into three suitcases, take them onto the plane and then erect the entire thing in Mexico in less than a week. We include that story in the book.

Staying with the textiles theme, there’s another piece where Hella Jongerius talks about her recent research into 3D weaving as a means of creating pliable architecture. Another interesting example is an essay looking at the evolution of the loom and how the Jacquard loom and punchcards were the start of computerisation and binary code.

We also have a piece written by author, Sally McGrane, about the women involved in sewing covers for NASA satellites and spacecrafts, called “A seamstress to the stars”. You know how marathon runners get given those silver blankets after running races? Well some of the satellites which are launched into space need to have similar thermal protection. They can’t be glued because no glue will withstand the heat, so they have to be sewn on. Sally interviewed a seamstress from NASA. It’s a fascinating story and it’s all in the book.

The latest chapter of the U-Joints research project, Knots&Knits, will take place at Fiskars Village Art & Design Biennale 22 May – 4 September 2022 as one of the main exhibitions. The full programme will be launched on 31 March and this is when the ticket sales begin. The book U-Joints – A Taxonomy of Connections will be launched in June and can be purchased from the biennial, too. More details can be found here.