Performance artist Teo Ala-Ruona on understanding, tenderness and spitting

Teo Ala-Ruona, Camille Auer and Alvi Haapamäki performing in Deep Time Trans. The working group also included Even Minn, Eeti Piiroinen, Satu Kankkonen, Emil Santtu Uuttu, Olivia Pohjola, Pihla Lehtinen and producer Riikka Thitz. Photo: Tani Simberg

Finnish performance artist Teo Ala-Ruona is known for explosive, visually strong pieces that explore aspects of gender, violence, love and the connection to one’s surroundings.

Ala-Ruona is a name that has recently been making the rounds in Helsinki. Anyone in the know would have seen the performer in pieces such as Lacuna, Deep Time Trans and My flesh is in tension, and I eat it? Known for his onstage body language that eerily creeps up to the viewer with a luscious dominance that demands attention, Ala-Ruona is an artist who believes in playing with the body.

Teo Ala-Ruona performing Lacuna. The working group consisted of Ala-Ruona, Tuukka Haapakorpi, Ami Karvonen and Sofia Palillo. Photo: Venla Helenius

This belief is something that began with jazz and contemporary dance classes when the performer was young. Strict choreographies performed as part of a group, moving in ways mapped by an external authority. This eventually made Ala-Ruona think that he was, in fact, not made for the stage.

“It was a predetermined aesthetic that we agreed to perform, yet it did not feel inviting to me. It felt strict and way too controlled. Instead, I enjoyed making music videos with one of my best friends, Maiju.

“We made our own music and danced to it. I think the songs were called something like Crazy today and Take this serious. I mean – the choreographies were actually pretty good.

“Even as a professional performer today, I find it hard to really connect with a piece if I don’t understand where the movement is supposed to come from or what it really aims to achieve. Even if the purpose is to look for the unknown, I need to know that.”

What this means in practice is that Ala-Ruona often works through strong visual cues, imaginative elements and scores. In Lacuna, for example, he envisioned opening his mouth so wide that the whole audience could fit in it.

“These types of magical elements and symbols work very well for me. I often thrive when given a fictional element – or a boundary – to work with. Something strong to strive for.”

While the artist might at some point have thought that he was not made for the stage, there was always a real calling to perform.

“I always wanted to perform, but there was just something lagging in the process. I feel that it was a very physical misunderstanding where I simply, in my body, could not understand why a plié or jump would just happen right here, at this certain point of the choreography.

“I did, however, enjoy the connection with the audience. I loved being onstage with them, moving for them.”

Particularly in his own pieces, Ala-Ruona is often seen moving like a beast possessed, body shaking, mouth gagging. Salivating like a rabid hound, near vicious.

“I believe that the aesthetic behind the way I tend to move began somewhere around 2013 when my friends and I established a performance art group called KIL. We were extremely dedicated to exploring what actually happens in our bodies.”

This meant exercises that were up to three to four hours long which aimed to examine bodily processes. Maybe nothing too enticing for the average viewer, but something vital when it came to building the way Ala-Ruona expresses himself through movement.

“I strongly believe in understanding the underlying causes and reasons for moving how we do in a piece. To me, it gives confidence to trust the process and what we are trying to do. I mean let’s face it, most of the time we are just adult humans crawling on the floor,” the artist laughs.

“Particularly when, looking up towards the audience while trapped in a highly compromising position – it becomes extremely important to know how I got there in the first place. And what I am actually trying to portray.

“When I am personally in charge of directing a group, I am very focused on trying to make sure that everyone understands why we are performing something. Sometimes that can be obvious to me too, but sometimes what I am trying to achieve is maybe just swaying – a motion that merely looks good. But even that then needs to be communicated.”

Is this something that translates to the viewer?

“When a professional performer is under duress, when you don’t quite understand the process, it might not always show. But what will most likely translate is a sense of triviality when the performer arrives at a waypoint and starts thinking which way to take. This is particularly problematic when there hasn’t been enough discussion on the backstory of the performance – when all is left open.

“A piece is always made up of several elements, but the ones that are important to me are energy and timing. When there is a lack of a bodily understanding, I will rush, and when I rush I become unable to maintain either the energy or the timing of that score. This is the crux – the moment when the viewer will see that I am finding myself in a space of discomfort.”

Is discomfort bad?

“No, no. What I mean is that it is completely OK to be able to let oneself and other performers alike land in discomfort at times, but the way I want to work is by creating work that is porous and breathing. That then means that while we, as performers, are often doing things that seem mundane or pretty basic like, ‘here I am dragging my body across the floor’ – we would still know the exact reason behind that specific movement.

“But don’t get me wrong. I am very interested in working with material that allows us to really fall, to really let go.”

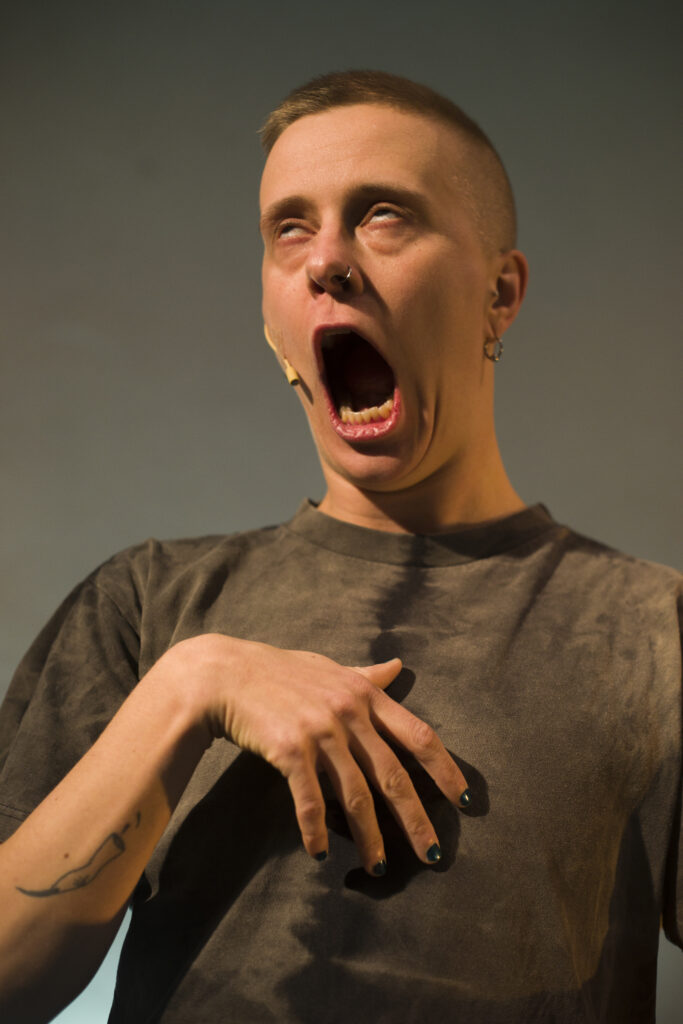

Teo Ala-Ruona

This for Ala-Ruona means working in a cognitive way, a way in which the body and mind remain symbiotic. Even though it sometimes happens that the head falls out of connection with the body, leaving the body to perform while the head starts thinking. Eyes now scanning the sea of people looking, the head might start asking questions like, ‘I wonder what that person is thinking’. This, according to Ala-Ruona, generates distance, a rupture in the performance.

“It’s the worst because I truly want to believe in each performance. But then suddenly I might look up and see all these people. I mean I always see them but in the magic of the movement I don’t question them or myself. If that feeling is broken then what happens is I start thinking of them looking at this adult me in a body spitting in someone’s mouth like, ‘Oh, look at us here, casually spitting on each other’.”

Ala-Ruona laughs, “Making a performance is so funny you know? Rehearsing for Babymmalian in their home, my colleague Anni Puolakka was nursing me while their partner was roaming aimlessly around us. And Anni is looking out the living room window saying, ‘I wonder if I should’ve closed the curtains’.

“Making art is fun. Excretion is fun.“

“I really believe in working with dramaturgy that allows for mistakes and play. This allows for our performative bodies to be vulnerable, slip up and lapse.

“It creates tenderness.”

Teo Ala-Ruona’s ENTER EXUDE-performance, May 2023 in Kiasma Theatre.